April 20, 2022

Proletarians of all countries, unite!

March 25th: 100 years since the founding of the Communist Party of Brazil (P.C.B.)

On March 25, 26 and 27, 1922, the Brazilian proletariat took its first great step in founding the Communist Party (1). There began the long and arduous struggle of our proletariat for the constitution of its revolutionary party. Initially adopting the name of Communist Party – Brazilian Section of the Communist International (PCSBIC), it began to unravel along the thorny and inhospitable road of the class struggle. This year marks the 100th anniversary of its foundation. On March 25 and in an effort to contribute to the liberation struggle of our people, AND republishes the article by Professor Fausto Arruda, written in 2008, which proposes a brief historical balance of the path and direction taken by the initiative of the pioneers of communism in Brazil. The article was published in two parts.

First part

“For some time now, on March 25, some political organizations, large and small, rush to celebrate the founding of the Communist Party of Brazil. These organizations commonly claim as their own this historic date for the proletariat and the Brazilian popular masses. In the ideological-political positions and practice of most of these organizations there is no identity with the great purpose of the founders of the party – there may be an identity with the heroic fighters of the Popular Uprising of ’35, the glorious Guerillas of Araguaia and so many others who shed their blood, in open combat or inside prisons and in torture, generously giving their lives to the proletarian cause – in fact it identifies itself with the opportunist, reformist and revisionist positions that for entire periods predominated in the the leadership of the party and the dark episodes of betrayal of the proletariat and capitulation that occurred in its leadership, making it succumb. The positions of those organizations are nothing more than the updated version of those rotten conceptions.

The path of the communist movement in Brazil has been very difficult and tortuous. In it the party made many mistakes, but it also accumulated great experience. It even reached a high level in its constitution as a Marxist-Leninist party. But at this moment of the class struggle and the world proletarian revolution, it was already required to be Marxist-Leninist-Maoist, which was not properly understood. In the leadership, faced with the dogmatism of some and the hard blows of the political police of reaction that eliminated the best cadres forged by the class, a position that capitulated from the revolutionary line of the people’s war ended up prevailing. Maoism was completely rejected and attacked and the party was liquidated as a revolutionary party of the proletariat. The proletarian revolutionaries, especially those of the new generations, must learn serious lessons and undertake the struggle for the reconstitution of the party, as a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist communist party in the fire of the class struggle, fighting imperialism and reaction inseparable from the struggle. revisionism and all opportunism, to raise the Brazilian revolution to new and great heights within the new wave of the world proletarian revolution that has already begun.”

From the testimony taken by a Maoist militant of the clandestine movement for the reconstitution of the Communist Party of Brazil.

Arising from the struggles of the newly-formed Brazilian proletariat and under the influence of the Bolshevik Revolution, but founded by militants, for the most part, coming from the anarcho-syndicalism in process of bankruptcy in the country, the Communist Party will be marked, in its first years, still by the legacy and reminiscences of this ideology. Founded as a communist party, and although it was soon admitted to the Communist International, in order to consolidate itself as such, as a Marxist-Leninist party, it will travel a long and complex road without, however, fully achieving it.

Throughout the decades, struggles between lines took place, sometimes openly, sometimes in a veiled manner, but continuously, as an inevitable reflection within the party, of the class contradictions of Brazilian society and of the international communist movement. Even if party members were not always fully aware of it. Struggle between the lines in the complex task of discovering the laws of the economic and social development of our country in order to establish the strategy and tactics of the Brazilian revolution. This is how the party will develop, passing through disintegration and reorganization, fragmentation and reconstruction, until its liquidation as a revolutionary party of the proletariat at the end of the 1970s. We can understand the development of its positions and its corresponding practice in three fundamental historical stages. The first, from the founding until the early 1930s. The second, from the early 1930s to the 1960s and the third, from 1960 to 1976. The third, the stage in which, in theory and practice, it was formed as a Marxist-Leninist Party.

First stage

In the struggle to assimilate Marxism-Leninism, struggling to overcome the anarcho-syndicalist heritage of most of its founders and the laborist and economist conceptions, the party will face the theoretical challenge of understanding the peculiar reality of the countries dominated by imperialism, which is dragging the secular backwardness of pre-capitalist relations, slavery and semi-feudalism.

In an attempt to break with economism, he took the shortcut of electoral reformism by organizing the Bloco Operário Camponês (BOC), withdrawing later with the harsh criticism of the CI. In its first eight years it held three congresses, and despite the theoretical effort of its staff, all were marked by the false, not to say naive, thesis of agrarianism versus industrialism. This thesis defended that the country was governed by a supposed contradiction within the dominant classes, which opposed the maintenance of the agrarian system to an industrializing process. The thesis that characterized the then stage of the Brazilian revolution as petty-bourgeois democratic made the same mistake.

Although the country was suffering the consequences of the crisis of overcoming the bankruptcy of the domination of the old slave oligarchies and was shaken from top to bottom by revolutionary bourgeois-democratic movements, the party could not play a leading role in this very rich revolutionary situation, lacking a scientific understanding of Brazilian society and a proletarian ideological-political line. The struggles in the party were restricted to detail problems due to the weak handling of historical dialectical materialism and the mass line to understand the national reality.

The party was practically absent and distant from the turbulent events guided by bourgeois-democratic aspirations, in which the most active sectors of the urban petty bourgeoisie fought in military movements for the simple exchange of representatives of the country (Tenentismo, Coluna Prestes and Aliança Liberal – “revolution of the 30”). This was a historical period of revolutionary effervescence aborted by the armed movement that succeeded Vargas’ Liberal Alliance and took state power by assault, betraying the bourgeois-democratic aspirations of the movements initiated with the so-called Tenentista Movement and culminating in the demobilization of the Coluna Prestes.

Second stage

The 1930s marked the beginning of a new stage in the life of the party. A stage that, due to its zigzagging characteristic between left and right in its orientation, will develop from the Levante Popular of 1935, culminating in the V Revisionist Congress of 1960. It goes through the crisis of disintegration after the New coup d’état of 1937 and reorganization with the CNOP (2) in 1943, through the struggle for the entry of Brazil into the war against Nazi-fascism on the side of the Allies, through the short life in legality (1945/46), through the Manifesto of 1948, the Manifesto of August 1950, for the important IV Congress (December/54-January/55), through the Declaration of March 1958. This long period of thirty years is marked by a permanent zigzag, which although it does not succeed in establishing a proletarian ideological-political line, it will pave the way for the development of the two-line struggle starting from the struggle against reformism and then against modern revisionism with the Reconstruction of the Party.

Although the party had advanced considerably in the assimilation of the basic theories of Marxism-Leninism, increasing its capacity of analysis of the Brazilian reality, it was deeply influenced by the newly-formed theses of modern revisionism, in particular Browderism (3). Theses of “peace and democracy”, of “convergence between socialism and capitalism”, which strengthened electoral opportunism and the dilution of the party in a “Democratic Front”, paving the way for its sinking and putrition in the Khrushchevist revisionism and in the opportunist reformism of the Prestista leadership of the following decades.

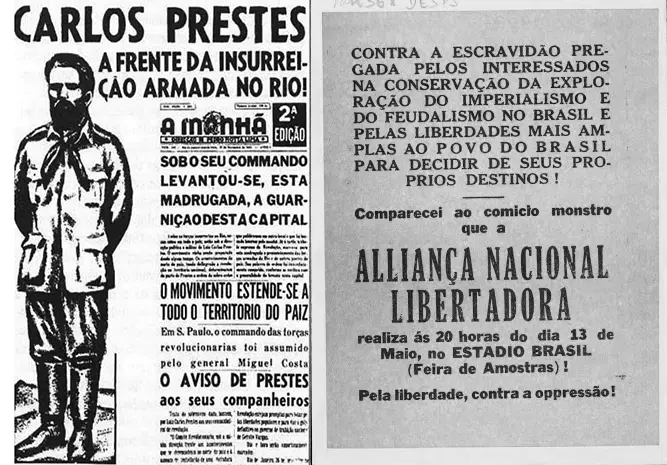

In 1935, thirteen years after its founding, the party made a qualitative leap in its process by establishing, in connection with the International Communist Movement, the road to the seizure of power through armed struggle. At this stage, when the forces of fascism had risen in Europe, the Communist International developed new theses of the united front of the working class to confront its expansion and to ward off the imperialist world war that was already brewing.

In Brazil, under the leadership of the party, the Alliance for National Liberation (ANL) was organized, a united front of revolutionary classes that advocated the establishment of a Popular Revolutionary Government, to confiscate imperialism, the big bourgeoisie and the semi-feudal landowners. The party already understood at that time the character of the Brazilian revolution as democratic, agrarian, anti-feudal and anti-imperialist, as a necessary step towards socialism.

At a moment that has become a historic milestone for our country and our proletariat, the party will carry out an armed uprising to seize power. In it, the party will make two fundamental mistakes: one of a strategic nature and the other of a tactical nature. In terms of strategy, it had not understood the role of the peasantry and this was a consequence of not having a deep knowledge of the social class process in colonial, semi-colonial and semi-feudal countries.

This problem was not simple, but already at that time Mao Tsetung had won the internal struggle of the CCP and his theses on the revolution in the countries dominated by imperialism were already known by the CI. Mao asserted that in the era of imperialism, democratic revolutions could only be carried out if led by the proletariat. He showed that the era of world bourgeois revolution had ended and the era of world proletarian revolution had begun. Therefore, it was no longer a question of democratic revolutions of the old type, carried out under the leadership of the bourgeoisie, but of democratic revolutions of the new type, uninterrupted to socialism. As a driving force this should be based on the worker-peasant alliance, with the peasantry as the main force and the proletariat as the leading force through the communist party. Mao had further formulated that the road was the strategy of encircling the cities from the countryside through a protracted people’s war. According to documents in the CI archives, there were clear indications from this organization to concentrate forces in the countryside, developing the armed struggle from the northeast of the country, an essentially agrarian region, dominated by semi-feudal large estates.

With the damage of the strategic error of completely neglecting the countryside, the tactical error was irreversible. To the extent that the Getúlio Vargas government hit the ANL by throwing it into illegality, temporarily isolating the party, the insurrectional plans were still maintained. This turned what was already difficult into a defeat of strategic proportions for the Brazilian proletariat. Reaction not only suffocated the armed uprising, but also extracted all the raw material from the incident to unite the discourse of counter-revolution, which will be used to this day (the “communist attempt”). The facts involve a paradox. Just as it was a transcendental moment in our history, when the proletarian party, still very young and inexperienced, at the head of a revolutionary class front (ANL) launched itself to the seizure of power, the defeat of the Levant will engender a profound reformism, lethally poisoning the party in the following decades.

Starting from false premises, whose basis is precisely the incomprehension of the particularity of the oppressed countries, the leadership of the party headed by Prestes will make a completely erroneous balance of facts. Assimilating the ideological attacks of the counter-revolution, it is concluded that the error was mainly of a coup character and that it was wrong to attempt against the Vargas government, which would be, in the new understanding, an ally of the proletariat in the democratic revolution. This understanding was fertile ground for the proliferation of Browder’s opportunist and revisionist theses. It is here that a whole opportunist right-wing line on the conception of the bourgeois-democratic revolution would emerge. Not only would they not understand the double character of the national bourgeoisie (middle bourgeoisie which has contradictions with imperialism and the local monopolies, but fear the proletariat), but they would take the Brazilian big bourgeoisie (particularly its bureaucratic fraction) for the national bourgeoisie (middle bourgeoisie). This, together with the peasant question, is one of the problems that historically the party has not known how to solve correctly, which will lead to enormous errors, deviations and will form entire generations in the ranks of the party in the crassest right opportunism.

Thus, the party torn by the savagery of the New Fascist State of Vargas will adopt incorrect policies of subjugation of the proletariat to the big bourgeoisie and the ways of electoral opportunism. With the end of World War II, with the prestige of the USSR and the communists on the rise in the world, the party, which had come out of hiding, was strengthened, instead of holding on to the tasks of preparation to launch itself into the struggle for the seizure of power, would get drunk on constitutional illusions. In spite of the great success obtained in the elections of the 46th Constituent Assembly, he was soon hit hard again. Once again in hiding and violently persecuted, he began, with the Manifesto of January 1948, a self-critical evaluation of the legalist illusions.

But, although under the cruelest persecution of the landowner-bureaucratic State in the service of imperialism, mainly Yankee, the party seeks to overcome such rightist deviations, clinging dogmatically to the European conceptions of insurrection and the mechanistic understanding of the Bolshevik Revolution, it will completely ignore the teachings of the Chinese Revolution and the gigantic contributions of Mao Tsetung.

Although the theses of the IV Congress, formulated in the wake of the Manifesto of August 1950, advocated the armed road to the seizure of power, the party will move towards a radical discourse without being able to fully put it into practice. The fact of continuing not to understand who was who in the Brazilian bourgeoisie, of not understanding the double character of the national bourgeoisie (middle bourgeoisie) and continuing to take the bureaucratic fraction of the Brazilian big bourgeoisie for the national bourgeoisie, besides continuing in practice to despise the peasantry, will be the propitious terrain for a new turn to the right. In spite of being considered leftist by various currents, the IV Congress will ultimately favor the prevalence of the old opportunism, assimilated after the defeat in the Popular Uprising of ’35, of the rightist line in the conception of the democratic revolution, this time under the banner of “national union”.

Under the allegation of the supposed leftism of the IV Congress and before the manifestations of discontent with its resolutions, Prestes, pulling to the right, as self-criticism to the “leftism of the IV Congress” which had begun to attack the Vargas. government, began to support the defense of the policy of support to the candidacy of Juscelino Kubitschek.

As soon as the revolutionary positions, although insufficient, accumulated in the IV Congress, were torn apart and crushed, serving as a point of support for the right wing to attack any truly revolutionary conception, and drag the party back into the swamp of opportunism. With the results of the XX Congress of the CPSU (1956), all the opportunism already rooted in the party gained cover and theoretical foundations. As Manuel Lisboa (4) would later say: “The decisions of the 20th Congress of the CPSU only gave legal and moral cover to reformism in the party”. With the famous Declaration of March 1958, the revisionist group of Prestes prepared the ground on which the V Congress, in 1960, consolidated Khrushchev’s theses on reformism and modern revisionism in the party. This statement deserved the harshest and most biting criticisms of Maurício Grabois5, who in the document “Two conceptions, two political orientations” unmasked its content of class collaboration for the capitulation of the Brazilian proletariat to the bourgeoisie and the reactionary Brazilian state. This fight cost Grabois his banishment from the central committee of the party.

1. The founding Congress took place in Niterói, with the participation of nine delegates representing nuclei of communists from different parts of the country. The delegates were: Astrojildo Pereira – journalist, Hermogênio da Silva Fernandes – electrician and railroad worker, Manoel Cendón – tailor, Joaquim Barbosa – tailor, Lui Peres – broom maker, José Elias da Silva – civil servant, Abílio de Nequete – hairdresser, Cristiano Cordeiro – civil servant and João da Costa Pimenta – typographer.

2. CNOP – Provisional National Organizing Commission – Created in 1942, led by Maurício Grabóis, Amarílio Vasconcelos, João Amazonas, Diógenes Arruda and Pedro Pomar, the commission was in charge of reorganizing the party after the coups of the Vargas dictatorship and of fighting against the liquidationist theses that were brewing in the Party. It held the II National Conference of the P.C.B., known as the Mantiqueira Conference and most of its members were elected to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Brazil.

3. About Earl Browder Secretary of the Communist Party of the United States in the years 1930/40.

4. Manuel Lisboa – Communist militant who joined the party at a very young age, participated in the process of Reconstruction and from 1966, together with Amaro Luiz de Carvalho, who was returning from studies in Popular China, broke with the PCdoB and organized in the Northeast the Revolutionary Communist Party. Manuel Lisboa fought against revisionism and expressed his positions in the important document Letter of the 12 Points to the Revolutionary Communists, with which he sustained the essential conceptions of Maoism for the Brazilian revolution, summarizing that “The nucleus of the strategy of the proletariat and its party is the people’s war through guerrilla warfare”. Manuel Lisboa was brutally assassinated in 1972, after more than 18 days of torture in the basements of the military regime in Recife.

5. Mauricio Grabois – Communist militant born in 1912. At the age of 18 he is admitted to the Party and soon after becomes responsible for agitation and propaganda of the Communist Youth of Brazil. He actively participates in the ALN and, later, in the CNOP. In the brief period of legality he is elected federal deputy. He participates in the process of rupture with the revisionism of Prestes and the reconstruction of the Party, now under the acronym PCdoB, when he approaches the thought of Mao Tsetung and contributes to the elaboration of the strategy of protracted people’s war outlined by the party. He was the commander of the Guerrilla Forces of Araguaia, having fallen in combat on December 25, 1973.

Third stage

The Fifth Congress, in 1960, would be preceded by an intense struggle within the party. The revisionists led by Prestes did not tolerate the internal struggle and expelled most of those who did not accept the cowardly attacks on Stalin. Even so, the struggle against opportunism gained strength. Pedro Pomar will lead, in the debates of the V Congress, the attack on the opportunist theses of national reformism. In 1962, the cadres who made up the revolutionary camp will carry out the struggle to purge the party of the revisionist group of Prestes. Being in a minority, they promoted a decisive split with the revisionists, initiating the process of Reconstruction of the party. This event will mark the beginning of a new and third stage in the history of the party, one of the richest and most important stages of its maturation that, in theory and practice, the P.C.B. (now under the acronym of PCdoB, to differentiate itself from the revisionist group) will be constituted in fact as a Marxist-Leninist communist party.

It is important to point out that the party was one of the first in the world to openly fight against the traitorous positions of Khrushchev. Mauricio Grabois’ letter to Khrushchev, in which he attacks his revisionist positions and in defense of Stalin, led Khrushchev to attack the Brazilian communists, citing them in the debates that arose with the Chinese Letter(1) in 1963. Also, before the V Congress (1960), Pedro Pomar, present at the congress of the Communist Party of Romania, strongly rejected the attacks on the leaders of the Party of Labor of Albania, absent from that event, made by Khrushchev who had accused them of adventurism.

This will be the stage in which the party will experience, for the first time, the open struggle against modern revisionism, by approaching the Mao Tsetung Thought (as Maoism was then called). Moment in which the struggle between Marxism-Leninism and modern revisionism will gain world dimension. Mao, at the head of this great battle, will unmask Khrushchev’s opportunism as modern revisionism, systematizing it in the formula of the “Three Peacefuls” and the “Two Wholes “(2). In the same period, the party will also have to combat the “left” opportunism, which arose as a reaction to the pacifism of the Prestes group (ALN of Carlos Marighella, MR8, PCBR, etc., and those of other processes such as VPR, Polop, etc.).

The Cuban Revolution, which had so much importance and transcendence for the struggle of the peoples of Latin America, ended up causing havoc, due to the fact that most of its leadership quickly aligned itself with Khrushchevite revisionism. The repercussion of the Cuban Revolution on the Brazilian revolutionary movement was very great and, consequently, the influence of its theses of petty-bourgeois revolutionary character. Conceptions that disregarded fundamental Marxist principles and postulates such as the need for proletarian leadership, expressed in the proletarian ideology and the proletarian party. These were then replaced by conceptions of “revolutionary fronts”, “left fronts” and military theories preaching militarism such as those of the “foquist” type. The phenomenon of this influence, moreover, is explained by the situation of asphyxia and revolutionary ardor held back by the reformism, pacifism, electoralism (children of revisionism) of the group led by Prestes. This sharp contradiction is broken by the easiest road, which disdains a hard and tenacious ideological struggle. Thus, thousands of Brazilian revolutionaries lost themselves in the “left” deviations, impatient to carry out a deeper ideological-political struggle, discovering the roots of the evil that so affected the revolutionary movement in the country and seeking the forge in the proletarian ideology. .

This will be a serious problem for the revolutionary movement, in spite of all the heroism demonstrated by so many fighters in the armed struggle against the pro-Yankee fascist military leadership. The PCdoB will also have to struggle against “left” opportunism, revealing it as a form of expression of Khrushchevite revisionism in Latin America (armed revisionism). (3) However, the party will not be able to free itself from serious deviations such as dogmatism. The leadership of the PCdoB, formed by experienced communist cadres, although it assumed Mao Tsetung thought, did so formally and bureaucratically, stagnating the internal struggle. It will not understand something essential of Maoism, the two-line struggle(4), as the correct method to forge the party. Such a misunderstanding will be crucial in preventing the party from fully assimilating Maoism.

The 30 years that will follow

the destruction of the party

(from 1978 to the present),

will be marked by obscurantism

the predominance of opportunism

in the popular movement

It will not examine or understand the true origins of reformism in the party. It will continue without a correct understanding of the Brazilian bourgeoisie, its fractions and its role in the class struggle. While the PCdoB advocated the Maoist strategy of encircling the city from the countryside, that is, taking the peasantry as the main force in the first stage of our revolution, it will not understand that, where the fundamental contradictions were most condensed in the countryside and the main one among them, was the northeast region and not the north, where the main strategic force would be concentrated.

By not understanding and not practicing the two-line struggle, it not only led to the split of the party (PCR under the leadership of Manoel Lisboa and Amaro Luiz de Carvalho, the Capivara and PCdoB Ala Vermelha (5)), but also made it impossible to develop the leadership in the correct understanding of the concept of people’s war. And that was the background of the defeat of the Guerrillas of Araguaia, as well as the blockage of its critical balance in the party and the consequent capitulation and complete rottenness after the death of most of the revolutionary cadres.

Important party documents will mark this period of the third stage of the history of the party: Letter of 12 Points to the Revolutionary Communists, from the PCR by Manoel Lisboa; Critique of the Union of Brazilians to Defeat the Crisis, the Dictatorship and Neocolonialism, by the PCdoB-AV and Prolonged People’s War, Caminho da Luta Armada no Brasil, by the PCdoB. Documents that address the theoretical question of the Brazilian revolution, guided by the contributions of Mao Tsetung and at the same time in conflict with each other on several issues. In addition, it is worth mentioning others by Pedro Pomar: Great Advances in the Cultural Revolution of 1969, on the development of the Great Cultural Revolution in China, A Gloriosa Bandera del 35, O Partido – Patrimônio Histórico and Sobre Araguaia, document on the balance of the experience of the Araguaia guerrillas.

Due to the total incomprehension on the question of the struggle of two lines for the leadership of the party, the defeat of the Guerrilha do Araguaia and the sabotage of the struggle for the correct balance of such an important experience, added to the elimination of the best communist cadres, completed with the incident of Lapa (6 ) (1976), the capitulation is inevitable. The capitulation of the revolutionary line of the people’s war headed by the leadership of João Amazonas led the party to the conversion to revisionism and its complete liquidation as a Marxist-Leninist party, transforming it into one more opportunist organization under the acronym PCdoB.

This capitulationist line, headed by João Amazonas, as a negation of the revolutionary road, could only be established in the party after the elimination of the main communist cadres in the leadership, supporters of the road of the revolutionary armed struggle. Without cadres more prepared to combat the revisionist subterfuges, Amazonas will find the way free to pass to the open and declared attack on Maoism, following the dogmatic-revisionist line of Enver Hoxha (7) to disguise its betrayal.

With the capitulation of the leadership, further reinforced by its complementation with cadres of the APML (8), the party became just another revisionist opportunist party. It will transform the heroic revolutionary experience of previous years into a dead icon, now used only as a “trophy” to continue deceiving the youth in search of political militancy. It will then be fully integrated into the official life of the old Brazilian State, in legalism, electoralism and parliamentary cretinism, up to the most degenerated situation it finds itself today as part of the old pro-imperialist bureaucratic order, as an auxiliary force in the administration of Luiz Inácio’s turn.

The events that will mark 1976 will be even more dramatic for the revolutionary movement worldwide. With the bourgeois restoration in China, driven by the coup d’etat of Teng Siao-ping, which will lead to the bloody massacre of the Maoist cadres, ends a whole long period, the first great wave of the world proletarian revolution, announced by the publication of the Manifesto of the Communist Party, in 1848, marked by the Paris Commune of 1871 as its “dress rehearsal” and boosted by the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917. In Brazil, the convulsions in the PCdoB in the years following the dramatic episode of Lapa, liquidating it as a revolutionary party, will culminate a very rich phase of the third stage of the party’s history.

The 30 years that will follow the destruction of the party (from 1978 to the present) will be marked by the obscurantism of the predominance of opportunism in the popular movement. The absence of the party of the proletariat, in the midst of the general offensive of the world counter-revolution, was the terrain for the erection of a real cartel of opportunism formed by the most harmful tendencies for the proletariat: the clerical, Trotskyist currents, the radical syndicalists disguised as yellow trade unionists, repentant ex-guerrillas and other renegades of Marxism-Leninism. All committed to join the anti-Stalinist chorus of world reaction on the “end of communism” and the “failure of socialism”. This agglomeration, to which revisionists of all acronyms came to join, was, after all, capable of reaching the top of the apparatus of the old reactionary state to play the role of its chief of the day. This situation, together with the great dangers and delays it represents for the struggle of the proletariat and the liberation of the Brazilian people, brought to light the true reactionary and pro-imperialist character of its positions.

Preste’s self-criticisms

Upon his return to the country, in 1979, Luiz Carlos Prestes broke with the organization he had led for almost 40 years. Unable to change the revisionist ideological-political positions already so crystallized in that association, in an exemplary self-critical effort he launched his Letter to the Communists, in a call to resume the revolutionary path. Undoubtedly, this gesture is indicative of his status as a communist, but the content of his self-criticism, which politically turns to the left, in ideological terms turned out to be very limited. He maintained the same hostility towards Stalin and his leadership taken from the trunk of Khrushchevite revisionism and did not even consider the extraordinary experience of the Chinese Revolution, that which was the highest stage of the world proletarian revolution – the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution – and even less the great ideologue and communist leader Mao Tsetung.

In the same way, he was deceived by Gorbachev’s Perestroika, which he understood as a movement for the recovery of socialism when, as was quickly demonstrated, it was nothing more than a revisionist maneuver aimed at raising a counter-revolutionary offensive on a planetary scale. However, unlike other recalcitrants who so much accused him of revisionism and were never capable of any recognition of their own revisionism, Prestes, with his self-criticism, alone, made a great contribution to the proletarian cause in Brazil. Prestes remains the greatest and main personality of the popular movement in the history of Brazil. The revolutionaries who today sincerely proclaim themselves followers of Prestes must make an effort to deepen the self-criticism launched by him, to understand that Marxism as a science is developing and that this development has already reached a third stage, Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, and that only under his leadership is it possible to reconstitute the Communist Party of Brazil.

To fight for the reconstitution of the party must be the task of the proletarian revolutionaries

However important the economic struggles of the workers, for the increase of wages and in defense of rights, will fail if they do not have in perspective the destruction of all order of the old bureaucratic state. Only with the construction of a new power, a new democracy expressing the interests of the oppressed classes and based on the worker-peasant alliance, which confiscates all the lands of the latifundia, capital of the big bourgeoisie and imperialism, will the transition to socialism be guaranteed. And this depends on the existence of a true revolutionary party of the proletariat. This is the lesson taught by the history of the communist movement in the world and in brazil. In the question of the existence or not of an authentic party of the proletariat, the communist party, armed with a scientific ideology, lies the crucial point, the advance or not of the revolution in the country.

As an expression of the worsening of the semicolonial condition of the country, the growing and inevitable intensification of the popular struggle will end up imposing itself. In the midst of the struggles of the poor peasants for land, against the semi-feudal landlord system, of the resistance struggles of the working class, the students, the women of the people and other popular classes against the state of misery and obscurantism present in our society, the revolution will develop. As popular resistance grows throughout the world, new fighters of the proletariat and the people are surely being forged for new revolutionary battles throughout the country. The implacable struggles against all opportunism, will gradually gather from the disillusionment with the sham electoral process, corruption, unemployment and hunger and all the other scourges that express the farce of an existing republic and democracy, the strength to raise the revolutionary and communist movement in brazil.

The task of the brazilian proletariat for its revolutionary party remains unfinished. But it should not be understood as the creation of a brand new party, nor as its “re-foundation”, anti-dialectical and anti-historical versions that reject the historical process as a whole. The communist party was created in 1922 and went through decades of stormy and complex struggles, reached a high level of its constitution, but was liquidated as a revolutionary party. The question for the true proletarian revolutionaries, who did not break or surrender in the face of the general offensive of the world counterrevolution, is the task of reconstituting it. To reconstitute it as a marxist-leninist-maoist communist party.

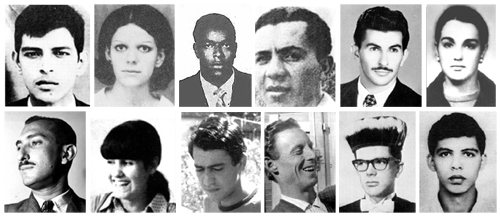

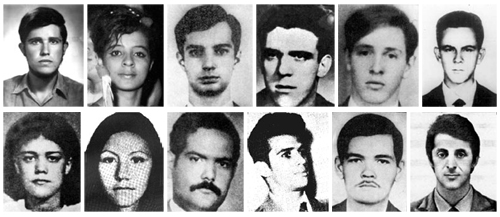

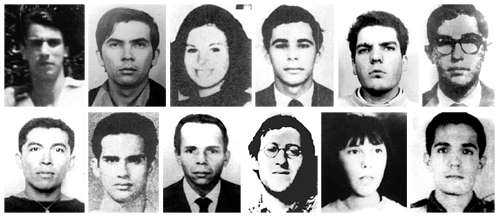

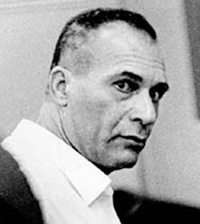

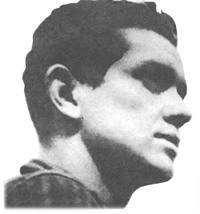

*The photos illustrating this article are of the heroic guerrillas of Araguaya.

1. Chinese letter – This is how the Propositions on the general line of the international communist movement, issued on June 14, 1963 by the Communist Party of China in defense of Marxism-Leninism and combating the theses of Khrushchev’s modern revisionism, were made known. In its letter of July 14, 1963 in reply to the Chinese letter, the CC of the CPSU called Grabois an “anti-party group”.

2. Three Peacefuls and Two Wholes – In essence, Khrushchev’s revisionist theses advocated “peaceful coexistence” not as Lenin had defined it in the early days of Soviet power as relations only between countries with different social regimes, but to regulate all relations between antagonistic classes. and between the dominated countries and imperialism; the “Peaceful Transition” with which he revised the Marxist concept of revolutionary violence, affirming that it was no longer possible to carry out social transformations by the revolutionary way, given the existence of the atomic bomb and the danger of a thermonuclear war, and furthermore, that the parliamentary way had become the way to reach socialism; The “Peaceful emulation”, with which he completed his revision of Marxism-Leninism on class struggle, advocating that the peaceful competition of economic and social development between socialism and capitalism would lead men to a general understanding of the superiority of socialism and, consequently, to its definition.

With the “Two Wholes”, the “Whole People’s State” and the “Whole People’s Party” he stripped the Socialist State and the Communist Party of their proletarian class character. He revised the Marxist-Leninist conception of the State, according to which it is a phenomenon of class society, being nothing more than “the special instrument of repression” of the ruling class. According to Khrushchev’s new revisionism, the State in socialism, the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, had lost its raison d’être and had become the State of “whole the people”, because in socialism there would be no more social classes. Consequently, from this conception it was derived that in the capitalist countries, bourgeois democracy in its parliamentary form would cease to be the Dictatorship of the Bourgeoisie, passing to the condition of the State of the whole people, to be contested and occupied peacefully by the proletariat … . As for the Communist Party, the revolutionary party of the proletariat had ceased to have a proletarian class character and had become the party of “all the people”.

3. This criticism of “left” opportunism is exposed in the documents of the PCdoB A Linha Revolucionaria do PCdoB.

4. Two Line Struggle – Concept developed by Mao Tsetung as a method to conduct the internal struggle in the Communist Party. It starts from the dialectical materialist conception that everything is contradiction, so the party is a unity of opposites, a contradiction. He affirms that within the party are reflected the class contradictions in society, the contradictions between the old and the new, between good and evil. Thus, communists who recognize the party as a contradiction must organize the two-line struggle to forge and defend the proletarian line against the bourgeois and other non-proletarian lines. Mao also draws attention to the need to know how to correctly manage the two-line struggle for the success of the party. He emphasizes that the struggle is to achieve unity at an ever higher level. In the general balance of the process of the Chinese Revolution, Mao speaks of the Ten Great Two-Line Struggles and their fundamental role in party building. During the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the slogan “criticism-struggle-transformation” was emphasized in the internal struggle of the party and in society, expressing the process of unity-struggle-transformation-new unity.

5. PCdoB Ala Vermelha – Party that arose from the disagreements of numerous militants of the PCdoB with the positions of the central committee and its theses for the VI Conference. Under the influence of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, they launched the document “Criticism of the Brazilian Union to get the country out of the crisis, defeat the dictatorship and neocolonialism”, harshly criticizing what they pointed out as opportunist deviations in the central thesis of the conference. This is an important document of the Brazilian communist movement which has two aspects. One that represents a just criticism of the theses of the central committee at the VI Conference and the other that expresses “foquist” deviations with respect to the conception of the people’s war. The intolerance of the central committee in not accepting the internal struggle and developing it led to the isolation of the sympathizers of the critique which later came to form the Communist Party of Brazil Ala Vermelha. In its Sixteen Points document, Ala self-criticizes the deviations present in the document Crítica ao União dos Brasileiros…, but soon abandons Maoism, defining itself then only as Marxist-Leninist and henceforth calling itself the Communist Party Ala rojA.

6. Lapa Massacre – Dramatic episode in which the safe house used for the meetings of the central committee of the PCdoB, in the neighborhood of Lapa, in São Paulo, was surrounded by a large operation of the Second Army. The components of the meeting were being arrested as soon as they were dropped off in distant streets. When the repression attacked the house with fire, it was the home of Pedro Pomar, Ângelo Arroyo and Maria Trindade. Pomar and Arroyo were massacred. João Batista Drumond, one of the prisoners when he left the place, was brutally tortured and murdered.

7. Enver Hoxha – Leader of the Party of Labor of Albania and leader of the Albanian Revolution. He took a stand in defense of Stalin in the face of Khrushchev’s cowardly accusations, as well as the decisions of the 20th Congress of the CPSU. Despite initially fighting against Khrushchev’s modern revisionism, during the Great Chinese Cultural Revolution he changed his position and became hostile to Maoism. Due to its dogmatism, it ended up revising positions previously taken in the struggle against modern revisionism, such as the recognition that classes and class struggle continue to exist in socialism.

8. APML – Organization that originated in revolutionary Christianity in the early 1960s, then adhered to Marxism-Leninism and in the late 1960s took up Maoism. In the struggle between joining or not joining the PCdoB, he was divided. The part that ended up joining the PCdoB quickly abandoned Maoism and its cadres took over the leadership of the party with the death of the best communist cadres the party had forged.

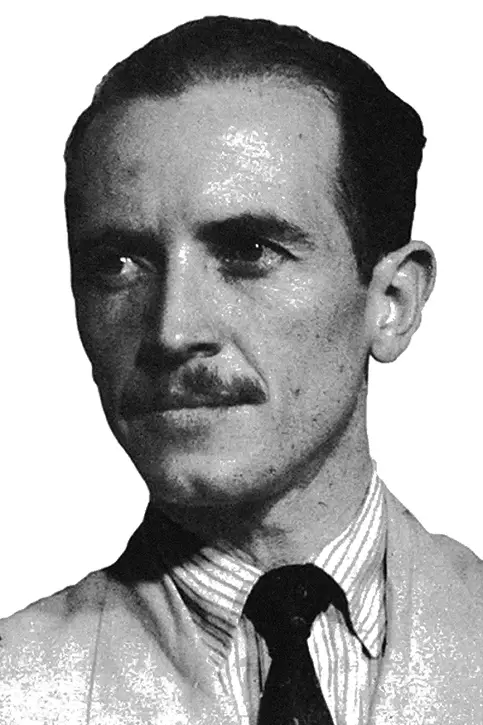

Outstanding leader of the P.C.B., Marighela was born in Salvador (Bahia, Brazil, on December 5, 1911) and joined the party when he was still young. Arrested after the defeat of the 1935 Popular Uprising, he was brutally tortured and spent many years in prison on Ilha Grande. Marighella was elected to the Constituent Assembly in 1946 and was active in parliament. He did not participate in the 1962 coup, but soon after the 1964 coup he broke with Prestes’ group and founded the ALN (Ação Libertadora Nacional) together with Joaquim Câmara Ferreira, getting closer to Cuba through OLAS (Latin American Solidarity Organization). His writings on guerrilla warfare and especially on urban guerrilla served as a guide not only to the ALN but to other revolutionary organizations in Brazil and Latin America. His righteous revolt against the bureaucratism, pacifism and opportunism of the revisionist parties led him to give greater importance to the fronts, sidelining the role of the party as the vanguard of the proletariat’s struggle. This misunderstanding, together with the adoption of militarist theories, lead him to make important errors of strategy. Marighella was assassinated by OBAN (Operação Bandeirantes, a repressive operation linked to the Brazilian Army barracks, located at Tutóia Street in São Paulo), in an ambush that counted with the help of Dominican friars and the command of delegate Fleury, on November 4, 1969.

Militant communist who joined the party as a youth, participated in the Reconstruction process, and from 1966 on, together with Amaro Luiz de Carvalho, who returned from studies in People’s China, broke with the PCdoB and organized the Revolutionary Communist Party in the Northeast. Manoel Lisboa fought against revisionism and expressed his positions in the important document Carta de 12 Pontos aos Comunistas Revolucionários, with which he sustained the essential conceptions of Maoism for the Brazilian revolution, summarizing that “the core of the strategy of the proletariat and its party is the people’s war through the guerrilla war. Manoel Lisboa was brutally murdered in 1973, after several weeks of torture in the cellars of the military regime in Recife.

Born in Óbidos, Pará, on September 23, 1913, he joined the Party early in the 1930s and in Belém he participated in the activities that led to the 1935 Popular Uprising. From his participation in so many struggles in the construction and organization of the Party and the struggle of the proletariat and the Brazilian people, we highlight some that demonstrate his stature as a communist and revolutionary chief. He participated intensely in the National Commission of Provisional Organization – CNOP and in the reorganization activities with the Mantiqueira Conference (1943) and in the propaganda activities by promoting the popular press. He took part in the revolutionary camp of the party’s central committee in the struggle against reformism, liquidationism and revisionism in the 1950s. In a scenario of extreme tension that the international communist movement was already experiencing, present at the 1959 congress of the Communist Party of Romania, as representative of the Communist Party of Bulgaria, he responded to Kruchov’s attacks on the Party of Labor of Albania, which was absent from the event. Against the current, he criticized Kruchov’s attitude and solidarized with the Party of Labor of Albania and the government of that country.

Already in 1960, as a delegate to the V Congress of the Party, he sustained a titanic struggle against the positions led by Prestes and launched by the Declaration of March 1958. Prestes’ central thesis, as to the characterization of Brazilian society, affirmed that the main revolutionary task was to promote the development of capitalism in Brazil. It was against reformist and anti-Marxist theses like this that Pomar placed himself in the first trench in defense of Marxism-Leninism.

As a prominent Party reorganizer in 1962 and a consistent anti-revisionist, he quickly identified in Mao Tsetung Thought the reinvigorated strength of Marxism-Leninism. In 1968, with his article Great Progress in the Cultural Revolution in China, he captured the significance of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that Chairman Mao was directing in China, claiming it to be a “resounding defeat for the counterrevolutionary world coalition of imperialism, reaction and contemporary revisionism.” … “By mobilizing masses of hundreds of millions, in a movement of unprecedented scope, the Proletarian Cultural Revolution, in less than two years, has already spread to the whole of China and has foiled the bourgeois revisionist plot aimed at the restoration of capitalism.” … “It is the inevitable result of the exacerbation of the class struggle in China and throughout the world.” … “The Proletarian Cultural Revolution has come to demonstrate the world-historical importance of Mao Tsetung Thought, as the Marxism-Leninism of our time.” And concluding, “The Brazilian Communists, who have received with enthusiasm the great successes of the Proletarian Cultural Revolution, seek to study its teachings and disseminate its experiences. At the same time they raise, higher and higher, the red flag of Mao Tsetung’s thought, which unveils for our people the path of revolution and the revolutionary war of liberation.”

Already after the defeat of the Guerrillas of Araguaia, in his struggle in the central committee of the party for making the correct balance sheet of that important experience he stated that “in Brazil the problem of the revolutionary path to free the people from exploitation and oppression has been very difficult. And the determination to tread it has become the touchstone of the different revolutionary forces, especially the Marxist-Leninists. Around the path, the conception and method of the armed struggle great divergences have always arisen.”

Concluding that the defeat in the Araguaia Guerrilla War had not only been of a “military and temporary” character as claimed by the Arroyo report and the position imposed by João Amazonas’ group, he demonstrated that its cause lay in a misunderstanding of the conception of popular war. Evoking the heroic and supreme sacrifice of the combatants of the Araguaia, Pomar defended the prolonged popular war, its scientific character and the military theory of the proletariat, and the need to understand the lessons of this experience and assimilate as deeply as possible the correct conception to resume and continue the revolutionary armed struggle and bring it to its triumph in the country. He concluded by affirming that “the flag of armed struggle that the comrades of the Araguaia wielded so heroically and for which they sacrificed themselves must be raised even higher. If we succeed in fact in connecting with the great masses of the countryside and the city and winning them to the orientation of the Party, no matter what the ferocity of the enemy, with all certainty the victory will be ours.”

Born on 02/12/1912, at the age of 18 he is admitted to the Party and shortly after becomes responsible for the agitation and propaganda of the Communist Youth of Brazil. He actively participates in the Aliança Nacional Libertadora (ANL) and, later, in the CNOP. During the party’s brief period of legality, he is elected to the Constituent Assembly (1946). He participates in the process of split with revisionism and in the rebuilding of the party (1962), now under the acronym PCdoB. Soon after the party’s rapprochement with Mao Tsetung’s thought, he contributed to the elaboration of the strategy of the prolonged people’s war outlined by the party. He was the commander of the Guerrilla Forces of Araguaia, and was killed in combat on December 25, 1973.